Music Iconography

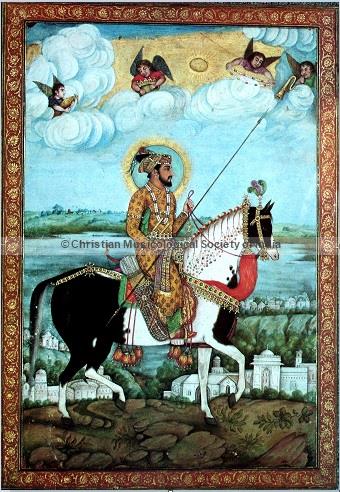

Shah Jehan with Angel musicians

Music Iconography in the Christian places of worship in India is intrinsically linked to the multi-layered history of Christianity and the extremely complex cultural history of the country. Musical instruments rarely find a place in the many murals, frescos and other art forms in Churches of the St. Thomas Christians in Kerala that were built or rebuilt before the sixteenth century. That scenario changed with the advent of the Portuguese missionaries who joined Vasco de Gama on his second voyage to Kerala, in 1502. These missionaries introduced Church architecture and interior decorations in the European style. In the subsequent centuries, the section of the St. Thomas Christians, who continued their allegiance to the Jesuits (i.e., Pope/Rome) after the Synod of Udayamperoor (1599) seem to have accepted the style of church architecture and interior decorations that the missionaries were familiar with in Spain and Portugal. The most important change was the wooden reredos on the altars that became a venue for exhibition of highly ornate, often gilded, artworks. These artworks include paintings and wood carvings of heavenly scenes with angel musicians, saints of the Roman Catholic Church, and even handsome men in European military uniforms. Angel musicians play mostly such Western musical instruments as the violin, trumpet, bugle, harp, drum, flute, and triangle. Among these instruments, violin appears much more frequently than others. So far, we see only one musical instrument of South Indian origin; this is a veena-playing angel inside the copula above the main altar at St. Antony=E2=80=99s Church at Ollur, in the Thrissur district of Kerala. This = church has a huge number of angel musicians painted on the walls, including angels who sing from a notation book. It would seem that the strategy of the Portuguese missionaries to use a visual medium to influence the way of thinking of the local Christians about liturgy and music worked in their favor. At the time of their representation in Kerala, these images provided a semblance of the future rather than a reflection of the present. It also was an indirect invitation to break away from the past and redirect the future by adopting these musical instruments along with the religious practices of the Roman rite (see Palackal 2004:159-161). Gradually, violin, triangle, and drum became part of the Syriac choirs in the Syro Malabar churches. In subsequent centuries, we see a complete transformation of the ideal sonority of Syriac chants in the Syro Malabar churches (see examples on tracks # 01, 21, 22, & 25, on *Qambel Maran: Syriac Chants from South India*, Palackal, 2002) Als= o, veneration of saints became a part of the religious piety in these churches. Chants in honor of the Roman-rite saints were translated into Syriac from Latin and composed anew in Kerala, sometimes employing indigenous musical idioms The study of music iconography in Christian churches in India is important not only for Christian music historians, but also for historians of music in India. Such a study might pose many challenges to music scholars. For example, the history of the violin in India may have to be pushed back from the British period to the Portuguese period, starting from the sixteenth century. The violin that one of the angels plays on the main altar of my native parish at Pallippuram, near Cherthala, Kerala, has five strings. We do not know if it were the result of an oversight of the artist, or if such violins were prevalent at that time in Kerala. The layers of cultural interaction between India and the Christian West may have had far reaching implications in Indian music. The transformation of the violin as an essential instrument in South Indian classical music is but one example. Currently, the images exhibited on this site are all from churches in Kerala. The Christian Musicological Society of India is indebted to Kuriachan J. Palackal for his extensive travels across Kerala to capture these images. We would appreciate if interested viewers would send us images from their respective regions in other parts of Kerala; that will widen the scope of this discussion. For instance, it will be interesting to compare the images represented in the churches in Kerala with those in Goa, where, unlike in Kerala, the Portuguese had complete control over the religious and political affairs of the new converts to the Roman Catholic form of Christianity. Christian Musicological Society of India welcomes comments and suggestions from viewers that will lead to a scholarly discourse. We shall gladly post those comments with proper acknowledgements. Please contact us at info@thecmsindia.org

*References*:

- Menacherry, George. 2015. Paḷḷikaḷile Chithrābhāsangaḷ (Malayalam, Paintings insides the Churches) . Thrissur:

- The South Asia Research Assistance Services (SARAS). Palackal, Joseph J. 2002. Qambel Māran: Syriac Chants from South India. CD and booklet. PAN Records, Netherlands (PAN 2085).

- 2004. “Interface Between History and Music in the Christian Context of South India.” In Christianity and Native Cultures: Perspectives from Different Regions of the World, edited by Cyriac Pullappilly, et al., 150-161. Notre Dame, Indiana: Cross Cultural Publications.

Iconography Gallery

-

-

St. Mary's Forane Church Champakulam

CMSI No. MI-9.12 (007-9.12)- Angels playing a Drum and a Daf -

St. Mary’s Forane Church, Kanjoor - (Ernakulam-Angamaly Archdiocese)

CMSI No. 007-8.12- Angel playing a Triangle -

-

Marth Mariam Forane Church, Kuravilangad-(Palai Archeparchy)

CMSI No. (MI-6.4) 007-6.4 - Angel playing a Bugle -

St. Mary's Metropolitan Church, Changanacherry- (Changanacherry Archeparchy)

CMSI No. (MI-5.2) 007-5.2 Angel playing a Bugle -

St. Mary's Forane Church Pallippuram -(Ernakulam-Angamaly Archeparchy)

CMSI No. MI-4.4 (007-4.4) Angel playing a Harp -

Infant Jesus Church, Thalore- (Trichur Archeparchy)

CMSI No. MI-3.4 (007-3.4) -Angels with a Harp and Violin -

-

Mar Sleewa Forane Church, Pazhvangadi Alappuzha

CMSI No.-007-12.11 Angels playing Daf amd Framed Drum

-

St.Joseph's Parish Shrine - Pavaratty, Thrissur

CMSI No. 007-13.3 - Angel playing a Trumpet

-

St. Mary's Forane Church, Valiapally-Kaduthuruthy

CMSI No. 007-14.1 - Angel Playing a Mandolin

-

St. Antony's Church, Ollur

CMSI No. MI-2.6(007-2.6) - Angels with Basson and Trumpet -

St. Joseph's Forane Church, Vaikom -(Ernakulam - Angamaly Archdiocese)

CMSI No. MI-1.12 (007-1.12) - Angel playing a Framed Drum -

-

St. Mary's Forane Church, Thazhathupally, Kaduthuruthy

CMSI No. MI-17.0 (007-17.0) - St.Mary's Forane Church, Thazhathupally, Kaduthuruthy -

St. Dominic Cemetry Church, Kaduthurthy

CMSI No. MI-18.0 (007-18.10) - Angel playing a Bugle -

St. Antony's Church, Thycattuserry

CMSI No. MI-15.0 (007-15.6) - Angel playing a Harp